Basic Estate Planning Principles

Estate planning relates to the arrangement of your affairs so that at the time of your death your assets will pass to those whom you wish to benefit, while being subjected to the least amount of taxes and transfer costs. Often, too, it speaks of setting things up so that your assets can be professionally managed for the benefit of less sophisticated loved ones when you are gone. Unfortunately, the Congress likes to change the tax laws all too often, so it is necessary to periodically review an estate plan once established to make sure your objectives will be carried out in light of changing law.

Trusts in estate planning

Living trusts have become the basic estate planning tool for medium to large estates. Trusts allow clients to cope with the six main estate planning problems:

- How to plan for disability;

- The expense of Probate at death;

- The problem of making lasting special financial arrangements for loved ones left behind;

- Delay in transferring assets on death;

- Privacy concerns; and

- Death taxes.

This article will explain how trusts can be used to deal with each of these concerns.

What is a Trust?

First of all, what is a trust? A trust is simply written instructions by someone called a “Settlor” (the person setting up the trust) to a “Trustee” (the trusted money manager) calling for the investment of assets (the “Trust Estate”) for the benefit of someone (the “Beneficiary”).

|

“Settlor” sets it up |

Trust = Instructions |

Trustee = Trusted money manager |

Beneficiary enjoys the money |

The best way to describe a trust is to give an example of a trust in action:

Parents often wish to make arrangements so that on their passing their children are provided for, without having money pass directly to them while they are young. Such parents can establish trusts which will invest assets, pay out money for the expenses of rearing young children, eventually pay for college, and then distribute trust assets when children are older and more experienced with finances.

Types of trusts – “living” vs. “testamentary”

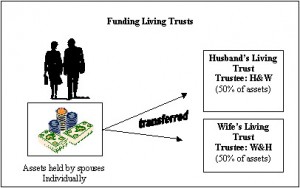

Trusts can be set up during life (“living trusts”) so that they can be used immediately, or they can be established through the provisions of a Last Will and Testament (“testamentary trusts”). Most modern estate plans use living trusts.

Typical “living” trust structure

Each trust requires a “Trustee.” These days there are numerous professional corporate trustees available, such as those affiliated with banks, stock brokers and other financial institutions. Many clients, however, desire to manage their own trusts for as long as possible to avoid paying Trustee fees. Thus, in the typical estate plan of a married client, the client forms a living trust, transfers his or her assets into the trust and then acts as co-Trustee of the trust along with the spouse:

Disability Plan

The back-up Trustee becomes Trustee on the death or disability of the Settlor and the spouse. This is a nice management device that avoids guardianship proceedings if the Settlor were to experience a health problem and become infirm. This allows the trustee, usually the other spouse, to act as sole Trustee, in the event of a disability, while still having a corporate trustee in reserve.

Avoiding “Probate”

Trusts don’t die, people do. Thus, even though the Settlor of a trust has passed on, a Trust holding the Settlor’s assets continues. One of the instructions to the back-up Trustee listed in the trust document is what to do with assets on the Settlor’s death. Sometimes assets are simply distributed outright to a spouse, or to mature children and in this case the living trust is simply a substitute for a Will – a substitute that avoids Probate. There is no reason to involve the Probate Court in the transfer of assets, where all of a decedent’s assets are owned by his or her trust. The cost savings in avoiding the Probate process can be considerable.

Making long term special arrangements for loved ones

Sometimes on death the Settlor has provided for the continued management by the trustee of trust assets for the benefit of children or a spouse. Oftentimes a trust is set up for children so that childhood expenses are paid for, college is taken care of and then a distribution of assets is made to children in stages when they have some life experience, say at ages 30, 35 and 40.

Speed and privacy

On someone’s passing, the surviving Trustee usually is in a position to quickly make the transfers called for in the trust. A typical Probate estate will remain open for at least six months.

Probate matters are a matter of public record. A living trust is an entirely private document.

“Revocable” trust can be undone

A living trust is revocable, which means it can be changed at any time. Even after you execute your Will, your trust can be modified without having to change your Will.

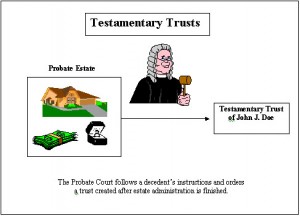

Testamentary Trusts

A testamentary trust can be useful (particularly, for younger couples because they are less expensive to arrange), but they do not avoid Probate, nor treat the other problems just mentioned. Again, a testamentary trust is one that is written in a Will. After a decedent’s death, the Probate Court orders the trust created at the end of the administration of the probate estate.

Sometimes testamentary trusts are a good idea when the client wants the administration of the trust to continue to be supervised by the Probate Court since a testamentary trust, after its creation, continues under the jurisdiction of the court.

Tax Consequences

Federal taxes

In substantial estates, one begins the planning process with the desire to keep state and federal death taxes to a minimum. Uncle Sam wants your money! He imposes a severe gift and estate tax on transfers to non-spouses above a certain amount.

Under the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 (TRA 2001), significant tax reform was achieved. Effective 2002 the amount excluded from taxation for Estate and Generation Skipping Taxes (GST) increased from $675,000 to $1,000,000. (Note that large gifts from grandparent to grandchild, can trigger an additional tax, the GST tax.) Additionally, a phased-in rate reduction was begun. In the year 2010 the tax was repealed entirely for one year.

Dramatic Changes in December 2010 for Two Years

In December of 2010 Congress passed a two-year extension of the Bush Tax cuts. The legislation also unexpectedly increased for two years the federal applicable exclusion amount (for both transfers during life and at death) such that an individual is temporarily now able to pass $5 million to a non-spouse beneficiary tax-free. Moreover, the exemption is “portable.” This means that (provided a federal estate tax return is filed for the first spouse to die) the estate of the surviving spouse is entitled to the portion of the credit of the first spouse to die that is unused. Thus, if the husband dies first with an estate of $2 million, the wife will be entitled to a total “deduction” for her own estate of $5 + $3 million = $8 million. The exemption also applies in the GST context, thus enabling grandparents to pass large gifts to grandchildren. The ability to pass up to $10 million tax-free to children and/or grandchildren for this brief period of time will be of great benefit to many family-owned businesses.

State inheritance taxes

Ohio imposes a smaller inheritance tax that begins at 6% and runs to 7% on amounts over $500,000. An estate under $338,333 is tax-free. Assets left to a spouse are exempt. Note, there is no gift tax in Ohio, which means that a gift (where the giver survives three years) escapes the tax that would have been imposed on the same transfer at death. However, effective in 2013 Ohio death taxes are repealed.

Availability of unified federal tax credit (“credit equivalent” deduction)

The current tax cuts sunset in 2013, at which time the old rules return and a tax-free estate becomes $1,000,000. This will enable one to pass to heirs $1,000,000 without any federal tax. It is vital to use this “credit equivalent” in each spouse’s estate.

Marital deduction allowed for assets passing to a spouse

An individual receives a deduction from the taxable estate for amounts passing to a spouse called the “marital deduction.” This means a husband and wife can transfer tax-free an unlimited amount of assets between them, either during their lives, or at the time of death.

Effective plan will be able in 2013 to pass $2,000,000 tax free

Again, in 2013 the credit equivalent deduction will enable a married couple to pass only $2,000,000 {$1,000,000 + $1,000,000} to their children, tax free. This objective will be able to be achieved while allowing the surviving spouse to be supported by all the couple’s savings for his or her lifetime. Careful planning will be required, however.

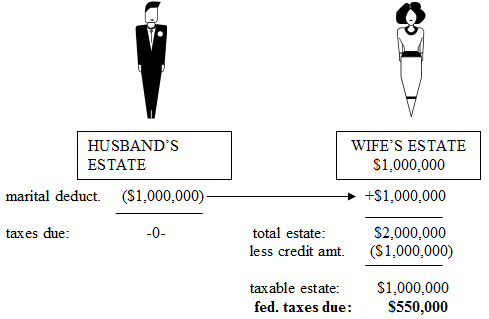

Example 1 – “I love you” estate plan

Here is an example of a “bad” 2013 estate plan: In this example each spouse has assets of $1,000,000 for a total of $2,000,000. The husband dies first and leaves his whole estate to the wife (“I love you darling, here’s everything…”). Things start well. Because of the “marital deduction,” the husband’s estate pays no tax:

The wife’s estate receives the husband’s assets and is then worth $2,000,000. After applying the credit equivalent of $1,000,000, the taxable estate is $1,000,000, with a federal tax consequence in 2013 of $550,000.

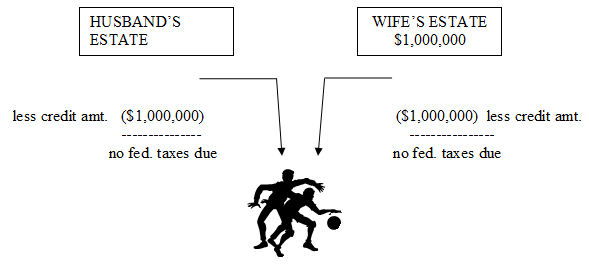

Example 2 – effective use of the “credit equivalent”

Here is an example of how the federal estate tax credit equivalent can be “captured” in both estates: In this example both husband and wife have estates of $1,000,000. Instead of leaving the money to the wife, the husband leaves everything to their children on his passing.

The wife also leaves everything directly to the children. The federal credit equivalent is completely used in each estate. Result – no federal taxes:

Need to balance larger estates so credit equivalent not lost

In order to be able to effectively utilize the credit equivalent that each person’s estate enjoys, it is necessary in constructing the estate plan that a certain amount of “balancing” be done with the assets owned by the husband and wife. In this regard, it is necessary that both husband and wife have in their individual names an amount of money adequate to use up the federal estate tax credit equivalent amount. Otherwise it would be lost!

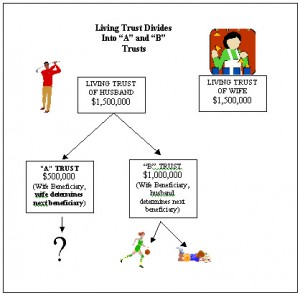

Structure of a basic estate plan using “A” and “B” trusts

Example 1 above demonstrated a bad estate plan – a lot of money was lost to taxes.

Example 2 offered some improvement. Two problems were apparent however. Dad died first, and the children got the money – it wasn’t made available to Mom. Secondly, the kids may not have been mature enough to handle the resources left them. These problems can be treated using trusts to take maximum advantage of the marital deduction and credit equivalent so as to minimize Uncle Sam’s share of the estate, and also to provide for asset management for children.

The “B” or “Bypass” trust

Here’s how it works: First we segregate an amount of assets into something called a “B,” or “by-pass” trust. In 2013 this trust will contain the credit equivalent of $1,000,000. This trust functions as sort of a “safety net” trust for the surviving spouse, keeping “B” trust assets apart from the surviving spouse’s estate and “bypassing” taxation in his or her estate – thus, the trust name. A surviving spouse can enjoy the income from the “B” trust, and will be supported by the principal of the trust, if the need arises. On his or her death, assets remaining in the “B” trust pass to children free of death taxes – even though the principal of the trust may have grown considerably.

The “A” or “marital deduction” trust

The other trust, or “A” trust will use the rule that allows an unlimited amount of money to pass to or for the benefit of a spouse tax free (thus, this trust is also called the “marital deduction trust”). In 2013 it will contain the balance of the spouse’s assets over and above the $1,000,000 that went into the “B” trust.

The “A” or “marital deduction trust” can be structured several different ways. Sometimes it contains a provision that gives the surviving spouse access to all of the trust’s assets. As such, the trust is merely used as a management devise. Here is an example of such a trust:

Assume a couple in 2013 with $2,500,000, with $2,000,000 in the husband’s trust and $500,000 in the wife’s living trust.

In the example, the husband dies first in 2013. The husband’s trust will now subdivide, placing about $1,000,000 to the “B” trust and about $1,500,000 to the “A” trust. The “A” trust will be taxable to the estate of the wife. The “B” or “by-pass” trust has been subject to taxation in the estate of the husband, although no tax was due, and will pass someday to children tax-free.

Sometimes, however, spouses desire to have assurance that, not only will the leftover funds in the “by-pass” or “B” trust pass to the couple’s children, but the assets in the “marital deduction” or “A” trust will do so, too. Many people are concerned with the surviving spouse remarrying and the money ending up with the new man or woman! This problem can be treated by use of a special trust, described below.

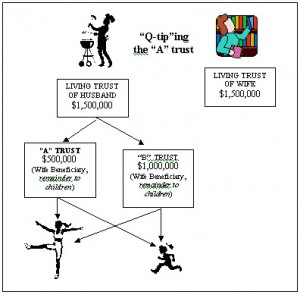

The technical name for trust property with “strings” on it is “qualified terminal interest property.” The initials from this phrase have generated the peculiar term, “Q-tip” property. When property passing to a spouse is “Q-tip’ed,” this means that strings are placed on the ability of the surviving spouse to control who gets the money left in the trust at his or her passing.

In this regard, the trustee of a marital deduction or “A” trust would be typically charged with providing for the liberal care, comfort, maintenance, and support of the surviving spouse, but the spouse would not have direct control of the principal. The spouse would get all income from the trust to use as he or she wishes. In addition, the trustee would be obligated to distribute such additional funds as are necessary to maintain the spouse in the standard of living specified.

Stated again: At the death of the surviving spouse, assets will pass to those persons that the first spouse to die originally selected. Usually this is the couple’s children. Here is an example of a “Q-tip’ed” “A” Trust, where the husband has designated the couple’s children as the ultimate beneficiaries. (The wife cannot change this.)

The wife then will enjoy $500,000 in her own living trust, the income from the $1,000,000 in the “B” trust, as well as the income from the $1,500,000 in the “A” trust. If she should use up all of this, the principal of both “A” and “B” trusts is available to support her. Thus, where assets are plentiful, the use of a Q-tip provision in the “A” trust should not unduly interfere with the survivor’s overall financial independence. It is also possible that the surviving spouse can be empowered to make the designation from among a group of persons. For instance: Sometimes one child needs more support than another. A surviving spouse might be given the right to choose which ones need the most support.

Life insurance and federal estate taxation

Life insurance can be both a curse and a blessing. One’s federally taxable estate includes the value of all life insurance of which the decedent was the “owner.” Incidents of “ownership” include the right to borrow against the policy and change the beneficiary. Therefore, clients who own their own policies are often well-advised to make their children the owners of the same, or, in the alternative, to make an irrevocable trust the owner.

The life insurance trust

Frequently, children are too young, or otherwise not appropriate individuals to own policies. Let us, thus, consider how a special irrevocable “life insurance” trust might be used.

A trust is created to be the owner of the life insurance policy. The client transfers his or her existing policies (or some of them) to the trust. The annual premiums on such policies are paid by the trust with funds that are gifted to the trust each year by the client.

Life insurance proceeds can be used to provide the liquidity to pay death taxes. Oftentimes a “second to die” policy is purchased on the lives of both husband and wife, since money for taxes is not needed until the second death. Such policies are usually affordable, even for older individuals. Thus, the life insurance trust and the by-pass trust must be coordinated to accomplish the objectives of the Settlor.

Other estate planning ideas

What follow are other estate planning ideas. Not all of them are appropriate for every client.

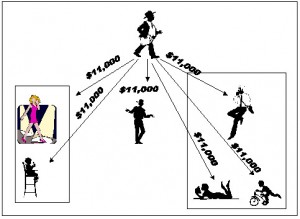

Plan of present gifting to reduce future taxes

The law provides one can give away $13,000 per year, per person, gift and estate tax-free. This amount will increase slowly in the future with inflation.

Where an individual is married and his wife joins in the transfer, that amount is increased to $26,000 per year. Even though the gift comes out of the wife’s assets, if the couple files a gift tax return and elects “gift-splitting,” the tax-free amount can be increased to $26,000.

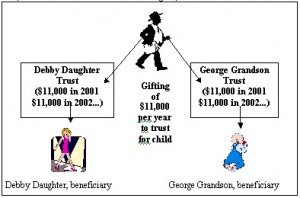

Sometimes, though gifting might be a good idea, children or grandchildren are either too young or inexperienced to receive the money directly. Additionally, sometimes it is feared that a child’s spouse might file for divorce and claim a share. Creditors are another concern. To deal with this, a client can establish trusts to receive gifts, for descendants’ benefit:

Choice of trustee

The choice of trustee becomes important. The trustee must be sophisticated enough to manage trust assets, while being attentive to your wishes and the needs of beneficiaries. With smaller amounts of money, it is difficult to find a bank or trust company to serve as trustee. A responsible family member can be used and siblings are sometimes made trustees for each other.

Trustee has discretion to pay out when needed; pays for college

As noted, such trusts could be set up for children or grandchildren who are receiving gifts or bequests. The trust instruments might provide that income and principal would be made available to the beneficiary as the trustee deemed advisable. For children who reach college age, the trustee could be directed to pay college expenses. Then, as the children get older, the trustee can continue to pay income and discretionary principal, prior to making disbursements of the principal in stages, say, when the children reach the ages of 30, 35 and 40.

High trust tax brackets means investing for the “long term”

There used to be very low tax brackets for trusts, which were attractive. These have been raised some years ago and are no longer favorable. The federal tax income rate on income a little over $10,000 is the maximum individual rate! Thus, investments in trusts, when a lot of current income is not needed, should be of the capital appreciating variety. Then, gains can be taken as capital gains, which currently are 15%, if they are long-term.

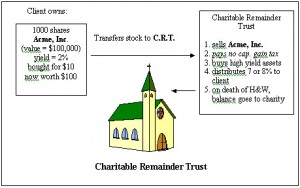

Charitable Remainder Trusts

A second technique for dealing with appreciated property is the establishment of a “charitable remainder trust” that will someday benefit a charity. The concept is fairly simple: One takes shares of low basis common stock upon which one would pay a big capital gains tax if sold and place them in a special trust for the charity.

The assets are sold, but because they are sold by the charity and not you, there is no capital gains tax due. Then, the proceeds are invested in high yielding assets. Before you held a highly-appreciated, low-yielding asset. Now, you can specify in the trust instrument that you want to receive as a payout from the trust, either a specific amount annually, or a specific percent of the trust corpus — say 8%. You get an immediate income tax deduction for setting up the trust, because the funds remaining in the trust pass to charity either on your death, or the death of husband and wife. This arrangement turns unproductive assets you cannot afford to sell into higher yielding ones, while giving you an income tax deduction against other income.

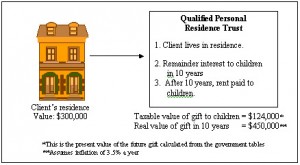

Qualified Personal Residence Trusts

After TRA 2001, many people continued to profit by transferring their residence to a special trust called a “qualified personal residence trust.” The idea here is to make a gift of one’s residence to children that will “kick in” some years — say 10 — down the road. This results in a much lower taxable gift to them. In the example below the gift of a $300,000 home in ten years is taxed as if a gift of $124,000 were being made today! This might not seem logical. In fact, this tax loophole exists because Uncle Sam makes an erroneous assumption. Consider this example:

Obviously, a house worth $300,000 today in normal times may well be worth more in ten years, not less, if there is any inflation. The government, however, assumes that the value of your house will not increase. It assumes that it will be worth exactly the same amount as it was worth when you placed it in the trust! Thus, your beneficiaries will likely receive that extra value tax-free. With a modest inflation assumption, the home will be worth $450,000. You remove $450,000 from your estate at a tax valuation of $124,000!

In the meantime, the client has the right to live in his or her home. If the client wants to remain in the home after the term is up, he or she is free do so, provided rent is paid. Remember, the idea is to get assets out of the client’s name.

The only drawback is that the client has to survive for the length of the trust — in our example 10 years. If not, then the house comes back into his or her estate and is taxed at its full value.

Retirement plan considerations

In 2001 the IRS greatly simplified and liberalized payouts from qualified retirement plans. Standardized withdrawal tables have been formulized that stretch out the time that persons have to withdraw plan assets after this process begins upon turning 70 ½. To achieve maximum flexibility, clients should name designated beneficiaries to all qualified plans. They should not name their estate beneficiary and charities and trusts should be designated as beneficiaries only with the assistance of an attorney. Note: spouses have the greatest flexibility as plan beneficiaries.

Tax apportionment

Clients need to think about who is going to be responsible for the payment of estate taxes. They should know that, even though assets do not pass through Probate, if living trusts or survivorship ownership arrangements are employed, there can still be an estate tax consequence. If no instruction is given, a situation might arise where the executor favored one beneficiary over another in this respect.

The client’s will should, thus, contain a “tax apportionment clause,” which specifies who is going to bear the tax burden and how tax basis is to be apportioned. In a typical Will, those taking from the residue (“all the rest residue and remainder shall pass to ….”) pay the taxes. It may well be that a client wants all those who inherit, (except a spouse, or a charity) either in the form of probate or non-probate property to pay a proportionate share of the estate and inheritance taxes. If this is the case, the client must insert the appropriate provision in his or her Will and trust.

Joint and survivor accounts not favored

As a reminder: Sometimes it happens that people will go to a lot of trouble to carry out estate plans, and then continue to own property in joint and survivor form, or, perhaps purchase property, such as annuities, that pass outside of both Probate and the tax planning provisions of a trust. These actions can destroy an estate plan.

Summary

Uncle Sam had made the tax laws incredibly complicated and the forthcoming tax law changes will only make matters worse. Some people are under the impression that inheritance taxes have been repealed. However, this was only for a single tax year—2010! This presentation is an attempt to simplify some of the more important estate planning concepts. Careful planning is more necessary than ever. The current federal and state tax structures will surely be changed over the coming years. Thus, it is vital to periodically review one’s plan. This article is to provide general information. Readers should rely on the information contained only after a professional relationship has been established.